İzmit Katliamı

| İzmit katliamı | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bölge | İzmit |

| Tarih | 24 Haziran 1921 |

| Ölü | 300'den fazla.[1] |

| İşleyenler | Yunan ordusu[1] |

İzmit katliamı 24 Haziran 1921 tarihinde meydana geldi ve İngiliz gazeteci Arnold Joseph Toynbee'nin tahminine göre 300'den fazla sivil Türk o gün öldürüldü.[1][2] Toynbee olaydan kısa bir süre sonra şehri ziyaret etti ve olayları belgeledi.[1] Olaylar Türk-Yunan Savaşı (1919-1922) sırasında Yunan kuvvetleri şehirden çekilirken meydana geldi ve şehir yağmalandı ve bir bölümü yandı.[3] 29 Haziran 1921 günü İngiliz parlamentosu Yunan çekilmesini ve olası zulümleri tartıştı.[4]

Arka plan

İzmit (Antik Nikomedia) İstanbul'a yakın kuzey batı Anadolu'da bir sahil kasabası. 19. yüzyılda burada Türkler, Yahudiler, Rumlar ve Ermeniler beraber oturuyorlardı. 1920 senesinde İngilizler şehrin yaklaşık 13.000 nüfusu olduğunu tahmin ediyorlardı.[5] Osmanlı İmparatorluğu I. Dünya Savaşını katılmış ve savaşı kaybetmişti onun üzerine galip Müttefik ülkeler arasında bölünmeye başlandı. Mayıs 1919'de İzmir'e Yunan ordusunun çıkması Türk milliyetçi hareketinin büyümesi ile sonuçlandı. Sonunda Yunan ve Türk milliyetçi orduları arasında savaş patlak verdi. Bu sürede İzmit önce 6 Temmuz 1920 yılında İngiltere tarafından işgal edildi ve daha sonra İngilizler 27 Ekim 1920 yılında şehri Yunanistan'a bıraktı. İzmit 28 Haziran 1921 tarihinde Türkler tarafından yeniden alınmıştır. Bu zaman sürecinde İzmit'i çevreleyen bölgelerde Türkler ve Rumlar arasında karşılıklı şiddet olayları yaşandı.

Toynbee'nin hatırası

Toynbee, eşi ve müttefik yüksek komisyon temsilcisi ile birlikte bir teknede İzmit'e doğru yol alırken karada Yunan ordusunun çekilmesini takip etti. Yunan ordusu bu alanı tahliye ederken çevredeki köyleri ve Karamürsel kasabasını ateşe verdiğini gördü ve[1][note 1] şöyle aktardı:

"29 Haziran 1921 günü karımla birlikte üniformalı Yunan birliklerinin bir neden olmaksızın İzmit Körfezi'nin güney kıyılarında yaptıkları kundakçılığa tanık olduk."[6]

Yerel Hristiyanların çoğu Yunan ordusu ile birlikte kaçıyorlardı.[1] [note 2] Toynbee İzmit'te Yunan çekilişinden 35 saat sonra şehre girdi ve şehri yağmalanmış ve kısmen yanmış buldu.[1][note 3]

Sahilde Yunanların mallarını taşımaya zorlanan ve sonra da kurşuna dizilen Türk arabacılarının cesetlerini gördü ve aralarında bir veya iki Türk kadın cesedi.[1][note 4] İzmit camileri, soyulmuş ve kirletilmişti, tarihi Pertev Paşa Camii'nin dışında ve içinde domuzlar kesilmişti.[1] [note 5] Türk dükkânları yağmalanmış, Hristiyan dükkânların yağmalanması ise üzerlerine bir haç işareti ile engellenmişti.[1][note 6]

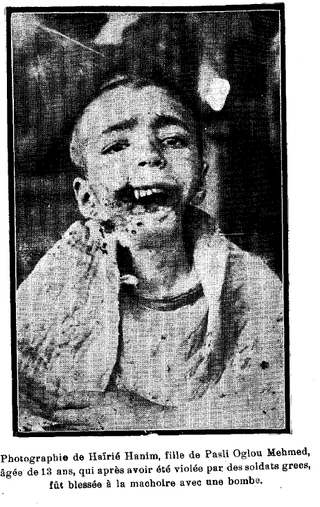

Toynbee'ye göre Türk nüfusunun genel bir katliam uğraması engellendi. Bunun sebebi öldürmeler başladıktan kısa bir süre sonra sokaklarda devriye gezmeye başlayan Fransız subaylarının çabalarını oldu.[1][note 7]Binlerce Türk mülteci Fransız papazlarının binasında korundu.[1][note 8] Fakat Cuma 24 Haziran'da, Yunan çekilişinden üç buçuk gün önce, iki Türk mahallesinin (Bağçeşme ve Tabakhane)'nin erkek sakinleri gruplar halinde mezarlığa götürüldü ve 300'den fazla Türk orada idam edildi.[1] [note 9] İzmitli Hristiyanlarının çoğu kaçmıştı ve neredeyse hiçbiri geri dönmedi, taşınmaz mallarını kaybettiler.[1] [note 10] Toynbee'ye göre, Yunan hizmetinde'ki Çerkesler İzmit'teki zulümlerde ikincil bir rol oynamıştı.[1][note 11]

Kaynakça

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1922). The Western question in Greece and Turkey. General Books LLC. s. 287–297–298–299. ISBN 9781152112612.

- ^ Özel, Sabahattin (2009). Millî mücadelede İzmit-Adapazarı ve Atatürk. Derin. s. 241. ISBN 9789756463024. 17 Temmuz 2014 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 12 Temmuz 2014.

- ^ Lieberman, Benjamin (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. s. 126. ISBN 9781442230385. Erişim tarihi: 8 Haziran 2014.

"In late June the Greek military gathered forces for the offensive by moving troops out of Ismid, leaving a looted city in flames. News of the Greek pullout caused panic among Armenian and Greek refugees who had found safe haven in Ismid.

- ^ "GREECE AND TURKEY". hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1921/jun/29/greece-and-turkey. British Parliament/ HANSARD.

but according to information received this morning the town of Ismid was evacuated by the Greek forces on the evening of 27th June. It is further reported that the town is in flames and that great panic prevails in the district. Numbers of Armenians and neutral Turks are fleeing towards Constantinople. Having regard to the general confusion, there appears to be considerable danger of massacres, and Mr. Rattigan, in concurrence with the Allied High Commissioners, is taking all possible steps to prevent such outrages by one side or the other.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. Londra: H.M. Stationery Office. 29 Eylül 2018 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 14 Haziran 2014.

- ^ Müderrisoğlu, Alptekin (2007). Sakarya: Yunan'ın Ankara'ya yaklaştığı günler. DenizBank. ISBN 9789944295017.

Toynbee'nin notları

- ^ On the 29th June 1921, my wife and I personally witnessed Greek troops in uniform committing arson without provocation along the south coast of the Gulf of Ismid. We were travelling up the Gulf towards Ismid in the Red Crescent S.S. Gul-i-Nihal, with a representative of the Allied High Commissioners on board, whose presence enabled us to pass the cordon of Greek warships. The Greek forces, which had evacuated the town of Ismid on the morning of the previous day, were retreating along the shore in the opposite direction—from east to west—towards Yalova and Gemlik. Our first intimation of their approach was the sudden appearance of two columns of smoke rising from the shore ahead of us. A little later, and a village burst into flames just as we came opposite to it, and at the same moment we saw that a column of Greek troops in uniform, coming from the east, had just arrived there. We were coasting only a few hundred yards from the shore, and could see the soldiers setting fire to the houses distinctly with the naked eye. Even the boats moored to the jetties were burning, down to the water-line. Later, as we looked astern, we saw new and larger columns of smoke rise from the little towns of Eregli and Karamursal, which had been intact a few hours before, when we had passed them. The head of the column had reached them and continued its operations. From our anchorage off Ismid that evening, we could see the fiery glow above Karamursal flickering far into the night. On the 1st and 2nd July we landed at Karamursal, Eregli and the skala of Deirmenderé, and walked up to inspect Deirmenderé itself. Everywhere the destruction had been malicious and systematic. Among the ruins of Karamursal we found two live human beings. One was an old Turkish woman named Khadija, who had been violated and beaten with rifle butts. The other was an exhausted Greek private named Andréas Masséras, belonging to the 10th Company, 16th Regiment, 11th Division. I afterwards got an account from him of what had occurred. During the retreat of the 29th June, he told me his regiment had been the rearguard—except for a detachment of Circassians only twenty or thirty men strong. The villages were all burning by the time that they reached them—a confirmation of our own observations at Ulashly Iskelesi, where we had seen the houses being set on fir by regular troops at the head of the column. At Eregli, Masséras had fallen out with sunstroke; the tail of the column passed him; he dragged himself on as far as Karamursal; collapsed there; and lay in the open till we picked him up. This again confirmed what we had seen for ourselves, that there had been no fighting during the retreat, and that the Turkish towns and villages had been burnt in cold blood, without provocation.

- ^ I must, however, say something about the events which preceded the voluntary withdrawal of the Greek Army from the town of Ismid, at the end of June 1921. During the year that the Greek occupation of Ismid had lasted (July 1920 to June 1921), the war of extermination had gone to such lengths, and the local Greek civilians had compromised themselves so deeply by participation, that the entire native Christian population took its departure with the troops. Naturally they felt savage. Their brief ascendency had cost them their homes; they had had to leave their immovable property behind; and though they had had time for preparations and the Greek authorities had provided shipping, their prospects were forlorn. They vented their rage on their Turkish civilian neighbours, while they still had them in their power.

- ^ One Turkish and Jewish quarter in the centre of the town had been set on fire, and the fire had only been extinguished after the Greeks’ departure by the exertions of the French Assumptionists (who have a College at Ismid, and covered themselves with honour on this occasion). Cattle had been penned into the burning quarter by the incendiaries in a frenzy of cruelty and had been burnt alive, and the smoking ruins were haunted by tortured, half-burnt cats.

- ^ The villages east of Ismid were evacuated first, and the Turkish peasants with their ox-carts were commandeered to transport the departing Christians’ possessions. When we landed at Ismid about thirty-five hours after the completion of the evacuation, the streets leading to the jetties were heaped with the wrecks of these carts and the water littered with the offal of the oxen, which had been slaughtered on the quay in order that the flesh and the hides might more conveniently be shipped away. Corpses of Turkish carters—murdered in return of their services—were floating among the offal, and one or two corpses of Turkish women.

- ^ The mosques had not only been robbed of their carpets and other furniture, but had been deliberately defiled. In the courtyard and even in the interior of the principal mosque, the Pertev Mehmed Jamy’sy, pigs had been slaughtered and left lying.

- ^ In the town itself, the Turkish shops had been systematically looted—the Christian shops being protected against the destroying angel by the sign of the cross, chalked up on their shutters over the owner’s name.

- ^ A general massacre had been prevented by the French liaison officer stationed at Ismid, who started patrolling the streets in company with the commander of a French destroyed as soon as the killing began.

- ^ They (French Assumptionists) sheltered several thousand Turkish civilians on their premises until the Greeks left, and when I visited them they were giving asylum to the one or two Christian families that had not got away.

- ^ But at 1 P.M. on Friday the 24th June, three and a half days before the Greek evacuation, the male inhabitants of the two Turkish quarters of Baghcheshmé and Tepekhané, in the highest part of the town, away from the sea, had been dragged out to the cemetery and shot in batches. On Wednesday the 29th I was present when two of the graves were opened, and ascertained for myself that the corpses were those of Moslems and that their arms had been pinioned behind their backs. There were thought to be about sixty corpses in that group of graves, and there were several others. In all, over 300 people were missing—a death-roll probably exceeding that at Smyrna on the 15th and 16th May 1919.

- ^ Their brief ascendency had cost them their homes; they had had to leave their immovable property behind; and though they had had time for preparations and the Greek authorities had provided shipping, their prospects were forlorn. They vented their rage on their Turkish civilian neighbours, while they still had them in their power.

- ^ At the end of June 1921, a few weeks after that report was written, some of these Circassian mercenaries assisted the Greek chettés and regular troops at Ismid in the massacre of Turkish civilians, on the eve of the Greek evacuation of the town. But so far as I could discover, they played a subordinate part, and there is no warrant for making them the scape-goats for either this or any other Greek atrocity.