Mutunus Tutunus

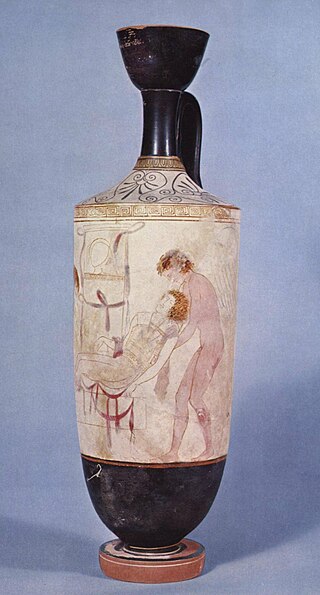

Antik Roma dininde, Mutunus Tutunus veya Mutinus Titinus, bazı açılardan Priapus ile eşdeğer olan fallik (phalus) bir evlilik tanrısıydı. Tapınağı, Roma'nın kuruluşundan bu yana, MÖ 1. yüzyıla kadar, Velian Tepesi'nde bulunuyordu .

Bu eylemi müstehcen bir bekaret kaybı olarak yorumlayan Kilise Babalarına göre, ilk evlilik törenleri sırasında Romalı gelinlerin, kendilerini cinsel ilişkiye hazırlamak için Mutunus'un fallusunu aşmış olmaları gerekiyordu.[1] Hristiyan apolojist Arnobius, onun "muazzam utanç verici parçaları" ile Tutunus yönettiği "korkunç fallusun" bir yolculuk (inequitare) için alındığını söylüyor.[2][3] 2. yüzyıl dilbilgisi ustası Festus, tanrıya dikkat çeken tek klasik Latince kaynaktır [4] ve ayinlerin Hristiyan kaynakları tarafından nitelendirilmesi muhtemelen düşmanca veya önyargılı olacaktır.[5]

Etimoloji

Büyük bir ereksiyonla insan formunda tasvir edilen Priapus'un aksine, Mutunus, Servius Tullius'un fascinus'u veya gizemli yaratıcısı gibi tamamen fallus tarafından somutlaştırılmış gibi görünüyor.

Mūtūnus Tūtūnus isminin her iki kısmı da tekrarlayıcıdır, Tītīnus belki de "penis" için bir argo kelime olan tītus'tan gelir .[6]

Kült

Velia'daki Mutunus Tutunus'un mabedi bulunamadı. Festus'a göre, en eski simge yapılardan biri olarak kabul edilmesine rağmen, pontifex ve Augustan destekçisi Domitius Calvinus için özel bir banyo yapmak için yıkıldı.[7]

Kaynakça

- ^ H.J. Rose, The Roman Questions of Plutarch: A New Translation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924, reprinted 1974), p. 84 online. 12 Temmuz 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.

- ^ Arnobius, Adversus nationes 4.7 (see also 4.11): Tutunus, cuius immanibus pudendis horrentique fascino vestras inequitare matronas et auspicabile ducitis et optatis. Compare Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11 and Apologeticus 25.3. On the translation of pudendis, see J.N. Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982, 1990), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Lactantius, Divinarum Institutionum 1.20.36: Tutinus in cuius sinu pudendo nubentes praesident ut illarum pudicitiam prior deus delibasse videatur. See also Augustine of Hippo (particularly De civitate Dei 4.11 and 6.9) who "several times refers with distaste to the practices associated with" the priapic gods; R.W. Dyson, The City of God Against the Pagans (Cambridge University Press, 1998, 2002), p. 1221 online.

- ^ Jean-Noël Robert, Eros romano: sexo y moral en la Roma antigua (Editorial Complutense, 1999), p. 58 online.

- ^ Ronald Syme, The Augustan Aristocracy (Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 6, note 37, marks "the mockery of the Christian writers"; see also Augustine's "distaste" for the phallic gods noted above. W.H. Parker, Priapea: Poems for a Phallic God (Routledge, 1988), p. 135 online 12 Temmuz 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi., observes that the ritual of Mutunus was "condemned by early Church fathers"; Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: The Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy, and the Ancient World (MIT Press, 1988), p. 159 online, notes that they spoke "scathingly" of phallic rituals. Tertullian's bias in his assemblage of deities to deride (including Mutunus) pointed out by Mary Beard, John North et al., Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 359, note 1 online. The fascinum — identified by Arnobius with the phallus of Mutunus — "was used by Christian writers in their tirades against pagan customs," points out Enrique Montero Cartelle, El latín erótico: aspectos léxicos y literarios (University of Seville, 1991), p. 70 online. For a fuller discussion, see Carlos A. Contreras, "Christian Views of Paganism," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.23.1 (1980) 974–1022, p. 1013 online specifically in relation to Mutunus and in general asserting that "Arnobius commits the same mistake as other Fathers of applying Christian conceptions to pagan ideas in order to condemn them" (p. 1010). "Our knowledge of such things," that is, of rites such as those of Mutunus, "comes from Christian writers who are openly concerned to discredit all aspects of pagan idolatry," states Peter Stewart, Statues in Roman Society: Representation and Response (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 266, note 24 online. 1 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.

- ^ Adams, Latin Sexual Vocabulary, p. 32.

- ^ Festus 142L, as cited and discussed by Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 262 online. See also Ronald Syme, The Augustan Aristocracy (Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 6 online.