Adolf Hitler'in dinî inancı

Adolf Hitler'in dinî inancı tartışma konusu olmuştur. Tarihçiler Hitler'i Hristiyanlık karşıtı görüşlere sahip olarak görmüşler[1] ve onu seküler bir teist olarak nitelendirmişlerdir.[2] Albert Speer'e göre Hitler, Japon dinî inançlarının veya İslamın Almanlar için Hristiyanlıktan daha uygun bir din olacağına inanıyordu.[3] Hitler, Hristiyanlığın yanı sıra ateizmi de eleştirdi.[4]

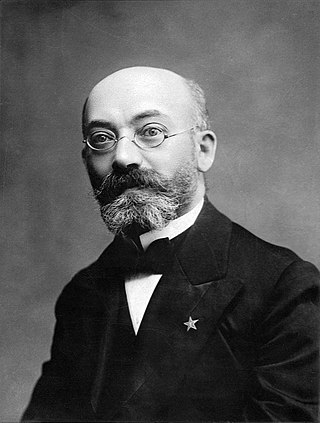

Hitler, Katolik bir anneden doğdu ve Roma Katolik Kilisesi'nde vaftiz edildi. 1904'te, ailenin yaşadığı Avusturya'nın Linz kentindeki Roma Katolik Katedrali'nde onaylandı.[5] Hitler ile Viyana'daki bir erkek evinde yaşayan birkaç tanığa göre Hitler bir daha pazar ayinlerine gitmedi ya da kutsal sayılan şeyleri evden ayrıldıktan sonra kabul etmedi.[6] Viyana'da erken yaşlarında ve 20'li yaşların ortalarındayken Hitler ile yaşayan birkaç görgü tanığı, 18 yaşında evden ayrıldıktan sonra kiliseye hiç katılmadığını belirtmişlerdir.[6]

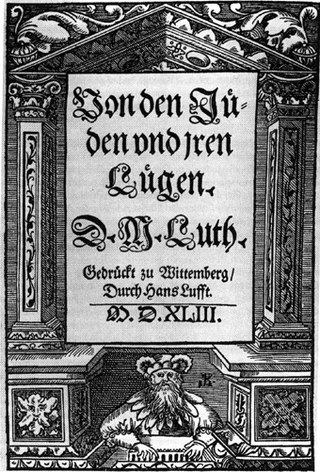

Hitler, Mein Kampf kitabında ve yönetiminin ilk yıllarında yaptığı konuşmalarda kendini Hristiyan olarak ifade etti.[7][8][9] Hitler ve Nazi Partisi "Pozitif Hristiyanlığı", İsa'nın ilahiliği gibi en geleneksel Hristiyan doktrinlerini ve Eski Ahit gibi Yahudi unsurları reddeden bir hareketi destekledi. Yaygın olarak dile getirilen bir açıklamada İsa'yı, "yolsuz Ferisilerin gücü ve iddialarına" ve Yahudi materyalizme karşı mücadele eden "Ari savaşçısı" olarak nitelendirdi. Bunlardan bahsettiği sırada Mein Kampf kitabında Hristiyanlığa "ruhani terör" de demiştir.[10] Aynı zamanda Mein Kampf'ta "tanrılar" ve "Tanrıça"dan da bahsetmiştir.[11] Nisan 1941'de günlüklerinde Propaganda Bakanı Joseph Goebbels, Hitler'in Vatikan ve Hristiyanlığın "sert bir rakibi" olmasına rağmen, "taktiksel sebeplerle" Kilise'den ayrılmasını yasakladığını yazmıştır.[12]

Hitler rejimi, birleşik bir Protestan Reich Kilisesi altında Alman Protestanların koordinasyonu yönünde bir çaba başlattı ve siyasi Katolikliği ortadan kaldırmak için erkenden harekete geçti.[13] Hitler, Vatikan'la Reich konkordatosunu kabul etti, ancak daha sonraki zamanlarda bu anlaşmayı rutin olarak görmezden geldi ve Katolik Kilisesi'ne baskı yapılmasına izin verdi.[14] Küçük dini azınlıklar daha sert bir baskı ile karşı karşıya kalırken, Alman Yahudileri Nazi ırksal ideolojisinin gereği imha edilmeye başladılar. Yehova'nın Şahitleri, Hitler'in hareketine hem askerlik hizmetini hem de bağlılığını reddettiği için acımasızca zulüm gördü. Her ne kadar siyasi nedenlerle çatışmaları ertelemeye hazır olsa da, tarihçiler nihayetinde Almanya'daki Hristiyanlığın yok edilmesini veya en azından onun Nazi görünümüne girmesini veya boyun eğdirilmesini amaçladığı sonucuna varıyorlar.

Ayrıca bakınız

Kaynakça

- ^ * Alan Bullock; Hitler: a Study in Tyranny; Harper Perennial Edition 1991; p. 219: "Hitler had been brought up a Catholic and was impressed by the organization and power of the Church... [but] to its teachings he showed only the sharpest hostility... he detested [Christianity]'s ethics in particular"

- Ian Kershaw; Hitler: A Biography; Norton; 2008 ed; pp. 295–297: "In early 1937 [Hitler] was declaring that 'Christianity was ripe for destruction', and that the Churches must yield to the 'primacy of the state', railing against any compromise with 'the most horrible institution imaginable'"

- Richard J. Evans; The Third Reich at War; Penguin Press; New York 2009, p. 547: Evans wrote that Hitler believed Germany could not tolerate the intervention of foreign influences such as the Pope and "Priests, he said, were 'black bugs', 'abortions in black cassocks'". Evans noted that Hitler saw Christianity as "indelibly Jewish in origin and character" and a "prototype of Bolshevism", which "violated the law of natural selection".

- Richard Overy: The Dictators Hitler's Germany Stalin's Russia; Allen Lane/Penguin; 2004.p 281: "[Hitler's] few private remarks on Christianity betray a profound contempt and indifference".

- A. N. Wilson; Hitler a Short Biography; Harper Press; 2012, p. 71.: "Much is sometimes made of the Catholic upbringing of Hitler... it was something to which Hitler himself often made allusion, and he was nearly always violently hostile. 'The biretta! The mere sight of these abortions in cassocks makes me wild!'"

- Laurence Rees; The Dark Charisma of Adolf Hitler; Ebury Press; 2012; p. 135.; "There is no evidence that Hitler himself, in his personal life, ever expressed any individual belief in the basic tenets of the Christian church"

- Derek Hastings (2010). Catholicism and the Roots of Nazism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 181 : Hastings considers it plausible that Hitler was a Catholic as late as his trial in 1924, but writes that "there is little doubt that Hitler was a staunch opponent of Christianity throughout the duration of the Third Reich."

- Joseph Goebbels (Fred Taylor Translation); The Goebbels Diaries 1939–41; Hamish Hamilton Ltd; London; 1982; 0-241-10893-4 : In his entry for 29 April 1941, Goebbels noted long discussions about the Vatican and Christianity, and wrote: "The Fuhrer is a fierce opponent of all that humbug".

- Albert Speer; Inside the Third Reich: Memoirs; Translation by Richard and Clara Winston; Macmillan; New York; 1970; p.123: "Once I have settled my other problem," [Hitler] occasionally declared, "I'll have my reckoning with the church. I'll have it reeling on the ropes." But Bormann did not want this reckoning postponed ... he would take out a document from his pocket and begin reading passages from a defiant sermon or pastoral letter. Frequently Hitler would become so worked up ... and vowed to punish the offending clergyman eventually ... That he could not immediately retaliate raised him to a white heat ..."

- Hitler's Table Talk: "The dogma of Christianity gets worn away before the advances of science. Religion will have to make more and more concessions. Gradually the myths crumble. All that's left is to prove that in nature there is no frontier between the organic and the inorganic. When understanding of the universe has become widespread, when the majority of men know that the stars are not sources of light but worlds, perhaps inhabited worlds like ours, then the Christian doctrine will be convicted of absurdity."

- ^ Weikart, Richard (2016). Hitler's Religion: The Twisted Beliefs that Drove the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. s. unpaginated. ISBN 978-1621575511. 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 31 Mart 2020.

It's true that Hitler's public statements opposing atheism should not be given too much weight, since they obviously served Hitler's political purposes to tar political opponents. However, in his private monologues, he likewise rejected atheism, providing further evidence that this was indeed his personal conviction. In July 1941, he told his colleagues that humans do not really know where the laws of nature come from. He continued, "Thus people discovered the wonderful concept of the Almighty, whose rule they venerate. We do not want to train people in atheism." He then maintained that every person has a consciousness of what we call God. This God was apparently not the Christian God preached in the churches, however, since Hitler continued, "In the long run National Socialism and the church cannot continue to exist together." The monologue confirms that Hitler rejected atheism, but it also underscores the vagueness of his conception of God. [...] While confessing faith in an omnipotent being of some sort, however, Hitler denied we could know anything about it. [...] Despite his suggestion that God is inscrutable and unfathomable, Hitler did sometimes claim to know something about the workings of Providence. [...] Perhaps even more significantly, he had complete faith that Providence had chosen him to lead the German people to greatness.

- ^ Speer 1971, s. 143.

- ^ Weikart, Richard (2016). Hitler's Religion: The Twisted Beliefs that Drove the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. s. unpaginated. ISBN 978-1621575511. 21 Ekim 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 31 Mart 2020.

It's true that Hitler's public statements opposing atheism should not be given too much weight, since they obviously served Hitler's political purposes to tar political opponents. However, in his private monologues, he likewise rejected atheism, providing further evidence that this was indeed his personal conviction. In July 1941, he told his colleagues that humans do not really know where the laws of nature come from. He continued, "Thus people discovered the wonderful concept of the Almighty, whose rule they venerate. We do not want to train people in atheism." He then maintained that every person has a consciousness of what we call God. This God was apparently not the Christian God preached in the churches, however, since Hitler continued, "In the long run National Socialism and the church cannot continue to exist together." The monologue confirms that Hitler rejected atheism, but it also underscores the vagueness of his conception of God. [...] While confessing faith in an omnipotent being of some sort, however, Hitler denied we could know anything about it. [...] Despite his suggestion that God is inscrutable and unfathomable, Hitler did sometimes claim to know something about the workings of Providence. [...] Perhaps even more significantly, he had complete faith that Providence had chosen him to lead the German people to greatness.

- ^ Bullock (1991), p.26

- ^ a b Rissmann, Michael (2001). Hitlers Gott: Vorsehungsglaube und Sendungsbewußtsein des deutschen Diktators. Zürich, München: Pendo, pp. 94–96; 978-3-85842-421-1.

- ^ John S. Conway. Review of Steigmann-Gall, Richard, The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945. H-German, H-Net Reviews. June, 2003: John S. Conway considered that Steigmann-Gall's analysis differed from earlier interpretations only by "degree and timing", but that if Hitler's early speeches evidenced a sincere appreciation of Christianity, "this Nazi Christianity was eviscerated of all the most essential orthodox dogmas" leaving only "the vaguest impression combined with anti-Jewish prejudice..." which few would recognize as "true Christianity".

- ^ Norman H. Baynes, ed. The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, April 1922-August 1939, Vol. 1 of 2, pp. 19–20, Oxford University Press, 1942

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1999). Mein Kampf. Ralph Mannheim, ed., New York: Mariner Books, pp. 65, 119, 152, 161, 214, 375, 383, 403, 436, 562, 565, 622, 632–633.

- ^ Mein Kampf, bölüm 5: "Felsefe ve Organizasyon", 1925. s. 454.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1925-1926). Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler - (Ralph Manheim Translation).

- ^ Fred Taylor Translation; The Goebbels Diaries 1939–41; Hamish Hamilton Ltd; London; 1982; 0-241-10893-4; p.340

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W. W. Norton & Company; London; p. 290.

- ^ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edition; W. W. Norton & Company; London p. 661."

Bibliyografya

- Speer, Albert (1971) [1969]. Inside the Third Reich. New York: Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-00071-5.

- Rissmann, Michael (2001), Hitlers Gott. Vorsehungsglaube und Sendungsbewußtsein des deutschen Diktators, Zürich München: Pendo, ss. 94-96, ISBN 978-3-85842-421-1.

Dış bağlantılar

- Mein Kampf 27 Mayıs 2022 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi. (İngilizce)